It’s hard to define the effect that the Japanese kimono has had on the international community. Between “inspiring” poorly designed and little researched robes that clearly cross lines of cultural appropriation, to admiration for the traditional kimono as an art form, opinions on this ethnic dress run the gambit.

But the fact is, most people don’t know much about Kimono at all. Western replicas are often robes, not actual Kimono. In fact, the actual art of kimono is rather complex and it’s incredibly common for an individual born and raised in Japan to meet with a professional Kimono stylist to get it right. This is especially true for plus-size kimono styling, which is still largely new to the industry.

To learn more about traditional kimono and contemporary kimono culture in Japan, I spoke with Osaka-based kimono stylist and teacher Jaenelle “Rin” Shiroshita about how her journey.

Meet the kimono stylist

Originally from Novi, Michigan, and part of the Japanese diaspora, Jaenelle Shiroshita of Mainichi Kimono has always been passionate about Japanese culture. But kimono, as a part of her heritage, always stuck out. Over the years, she gravitated more and more towards learning the skills required as a stylist.

The fact that the kimono has been so misunderstood and appropriated was the final push for Jaenelle to turn her love for kimono into a life calling.

“In 2019, when the Kim K scandal happened regarding the attempted trademark of the word “kimono”, I was reading about it in the news and happened upon an article discussing being a professionally licensed kimono stylist,” says Jaenelle. “I thought that this was something I could do not only for myself but to help other Japanese diaspora groups to do more to introduce the world to kimono. A few months later, I moved to Japan from China and began my journey as a kimono stylist.”

Let’s define kimono for a hot second

Kimono is famous for being the traditional dress of Japan, and the word itself comes from the characters ki (着; to wear) and mono (物; thing). Before the Nara period (710-790), Japanese traditional clothing looked extremely different, and the influence of China’s Tang Dynasty on Imperial Court life in Japan had a major impact on how the kimono would evolve into what it is today.

During the Edo period, the predecessor of the modern kimono, called the kosode, had become a key element of ordinary Japanese fashion. Like many traditional garments across the world, an individual’s kosode could be linked to their status or region. The design, fabric, color, and technique used for each kosode were indicators of a person’s gender and socio-economic status.

When we talk about the modern kimono, there are a few things to consider. We have different types for different occasions, and they are made from a wide range of fabric options, not only silk. There are even fusion kimono styles that mix traditional and contemporary fashion.

It’s also important to note that kimono doesn’t just refer to women’s clothing. Men’s kimono is just as traditional and important.

Today in Japan, the traditional dress is usually reserved for special occasions such as weddings, coming-of-age ceremonies, a baby’s first shrine visit, and other important hallmarks in a person’s life. However, most Japanese actually cannot put on a kimono by themselves.

“It can be pretty complicated and overwhelming, and so if you wish to learn and you don’t have a relative to teach you, you can either try to learn at school, through online tutorials, or find a teacher/tutor such as myself,” says Jaenelle.

If you look at western “inspired” robes and compare them to the formal kimono, it’s easy to see the disconnect.

Kimono is all about layers.

What you need to start learning kimono

Learning how to dress in kimono, or “Kitsuke” (着付け; “dressing”, especially in regards to kimono) can be very overwhelming at first. There are so many more layers than simply the kimono robe and the obi belt, and so many items you need to keep it all in place.

The steps for kimono dressing can be basically summarized as:

- Kimono “underwear”

- Nagajuban

- Kimono

- Obi

Kimono “underwear” consists of hadajuban (肌襦袢; undershirt) and susuyoke (裾除け; skirt). For most people wearing kimono by themselves, we usually put on the Hadajuban and Susoyoke over our regular underwear, or perhaps a slim-fitting tank-top and leggings that go to your knees or mid-calf. For Jaenelle’s dressing clients, she usually has them put on a one-piece kimono slip for convenience.

After you’ve got the underwear on, you need the padding. A kimono consists of eight different cut rectangles, and to accommodate this, the “ideal” body shape for kimono is a cylinder, so we want to eliminate curves. You can wrap the body around the waist with thin, long towels or you can even sew your own padding out of towels.

“This padding is so fundamental to the basics of kimono that on my first day of kimono school, the very first thing I did was make padding out of the towels,” says Jaenelle.

After that, it’s time to put on the nagajuban (長襦袢), which looks like a white kimono robe that goes underneath the top-most layer. However, it’s not a kimono, but instead, a kimono-shaped undergarment that protects the top layer from sweat. Fabrics such as silk can be stained with sweat, and with all those layers on, you are going to sweat no matter what. Furthermore, kimono can be very difficult to clean, and it’s much easier to clean a nagajuban.

If you’re not used to sewing, you can use a himo cord to tie the towels around your waist and keep them secure.

Perhaps you may have noticed that the back of a kimono doesn’t touch your neck. To keep the garment off the back of your neck, you need an erishin ( 衿芯), a long piece of plastic that is inserted into the nagajuban collar. This keeps the collar stiff and prevents both kimono and nagajuban from touching your neck. We tie the nagajuban with a datejime (伊達締め) belt that secures the nagajuban.

“This is the step where we finally put on the kimono! It takes a lot of practice to get it right; it took me about three months to become halfway decent at it,” says Jaenelle.

On top of learning how to put on the kimono properly, we also need to have the right tools to secure it. First, you need the waist belt: After the waist belt and adjusting the kimono, you need yet another kimono belt! This one has clips to prevent the kimono from opening – so don’t forget it.

Finally, you need another datejime, but this one is specifically for wearing around the waist of the kimono. The final tool needed is the obi-ita. This keeps the obi flat and straight against your body because you will be walking, and you want to make sure that when you tie other things like obijime that it doesn’t wrinkle or scrunch up!

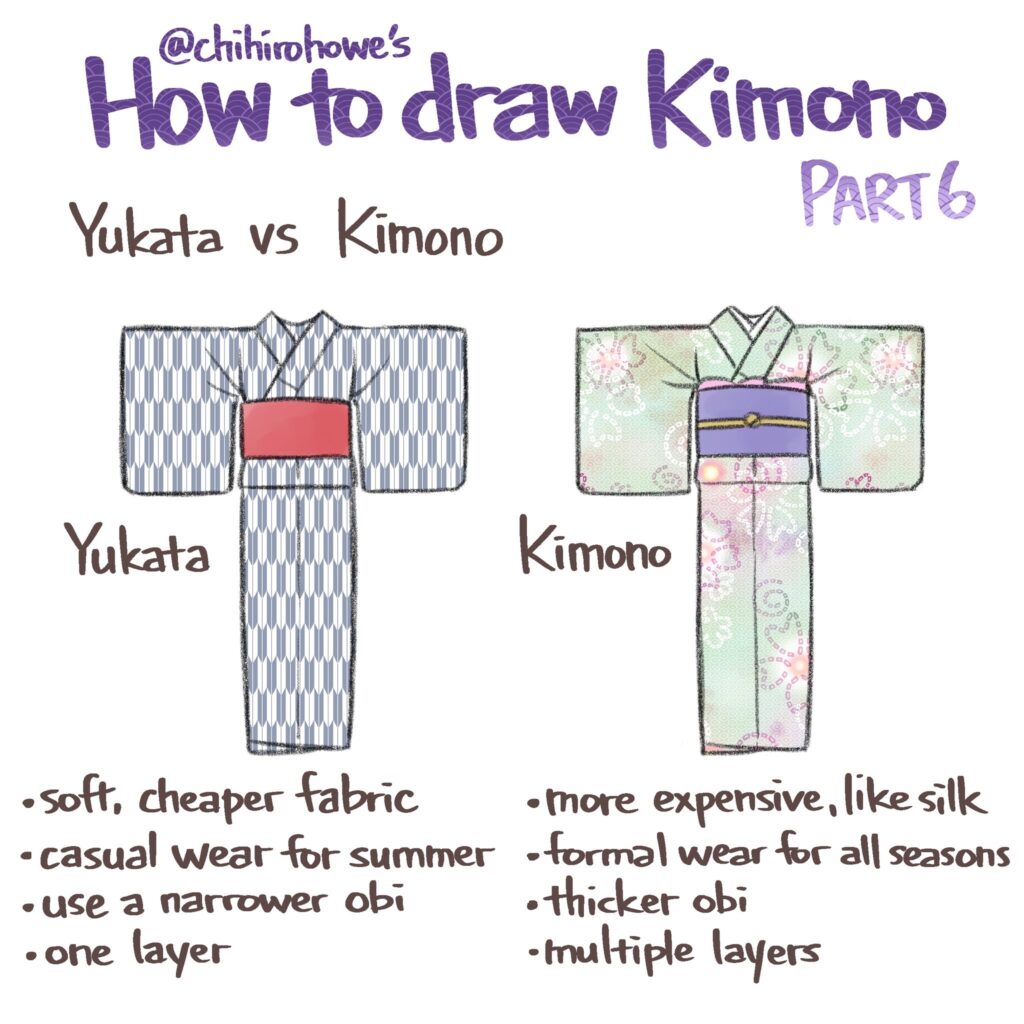

The difference between kimono and yukata

Outside of the formal kimono, there is also a more casual traditional clothing called yukata. There are a few key differences between the two, namely:

- Yukata has a half-width single collar, while kimono has a full-width double collar

- Kimono sleeves vary and length, but the sleeves on the Yukata never exceeded 50cm

- Yukata is normally made of a lighter material and is more common in the summer

- Yukata is worn for casual occasions, such as summer festivals, while kimono is normally worn for important life events

Both the yukata and kimono come in a wide array of styles, patterns, and colors.

The beginnings of the modern kimono school

Before WWII, kimono was much more common in a Japanese person’s daily life. However, after WWII a lot of Japanese families were suffering economically. Either they could not afford new kimono, couldn’t repair damaged kimono, or they were forced to sell kimono in order to survive financially.

Western clothing, which was much cheaper and easier to wear, became what was worn on a daily basis. As a result of this, we have today’s current situation where kimono and other traditional Japanese garments are mainly reserved for special occasions.

In an effort to preserve the art of kitsuke, in the 1970s kimono schools began to emerge. There is no singular authoritative school for kimono, and as such different kimono associations focus on different things.

Some kimono schools require two or more years of study before you can get your license, some require only one. Some kimono schools focus on speed dressing and other schools have other specializations. Not all schools offer the same thing, and not all schools teach the exact same way to tie more common obi musubi (obi knots). Because of this, some people study at several kimono schools, and others may choose to stay with only one.

“The initial study for my license at my kimono school was one year,” says Jaenelle. “Some kimono schools have longer courses, but in my observation, they cover roughly the same material, give or take.”

Her kimono school offers three stages: 本科 (honka; regular, basic), 専科 (senka, specialized), and 師範 (shihan, instructor/master).

“I achieved shihan rank, but I feel that I still have so much to learn and will be learning the rest of my life, so I don’t really feel comfortable calling myself ‘master’!” says Jaenelle.

The honka stage (3rd rank) is the very basics of kimono. Most people who do not wish to become professional in kimono but want to learn how to dress themselves will take this course only.

The senka stage (2nd rank) is, as the name suggests, more specialized, and it’s when you truly begin to learn how to dress others both formally and informally.

The final stage, shihan, goes into even more knowledge about formal dressing for kimono and you start to prepare for the final exam that will grant you your license.

At the end of each stage, there is an exam.

The first part of a kimono exam at Jaenelle’s school is written and yes it’s all in Japanese. Some of it is multiple choice, labeling parts of a kimono, matching (i.e. match the type of obi with the type of kimono and what kind of situation), and a little bit of writing.

The second part of the exam is the dressing part. You stand in front of a panel of judges and you are timed.

For rank 3 and rank 2 exams, you have 15 minutes to dress yourself. They grant you a little bit of mercy and you begin from nagajuban instead of the very beginning. For rank 1, only 12 minutes. Rank 1 also requires that you dress someone else (or a mannequin) in formal kimono. You are not allowed to look in the mirror while you’re dressing.

After you have finished dressing yourself and time is called, you have a couple of minutes to finally look at the mirror and make any quick, minor adjustments. From there, you wait for your name to be called and you greet the judges then let them evaluate you.

They judge everything from how neat the kimono is sitting on your body to even the distance from the floor the bottom of the kimono is, how straight the obi knot is if anything is too small, too wide, too short, etc. And of course, how elegant of a job you’ve done and if your movements and hands were elegant while dressing.

Getting into Kimono school

There is no visa for kimono school. If you want to learn this tradition in Japan, you have two options:

- Take a one-day course on a tourist visa, or

- Invest in a longer licensing course while on an employement or student visa.

Licensing courses outside of Japan are few and far between. One example is the various certificate classes from Kaede NYC.

Supporting Kimono Artisans and Stylists

Today, there are many ways of supporting the kimono industry. A lot of “factory line” rental shops, especially in places like Kyoto, where they promise to dress you quickly (like 5 minutes!) are a good introduction to kimono for tourists, but to be entirely honest most of their kimono are mass-produced (often outside of Japan for cheap), and don’t support actual kimono artisans. However, it can be very intimidating when you see a kimono for $500 or more!

A good suggestion is to support stylists who use authentic kimono when dressing clients.

For dressers, check if they’re truly knowledgeable in kimono; it can be easy to impress someone online with a halfway decent knowledge of the basics, but someone who has a real family history with kimono or a license (shihan; 師範) will understand kimono much deeper than a hobbyist trying to make a quick profit off of Japanese culture enthusiasts.

Secondly, there are places in cities like Kyoto and Kanazawa where you can go experience kimono dyeing workshops such as the Kaga-Yuzen museum and Marumasu-Nishimuraya. If you cannot afford a kimono made with these techniques, it is a wonderful chance to experience it firsthand while still supporting artisans. Take a look at websites such as Airbnb experiences or Voyagin and find local hosts for kimono-related experiences.

Finally, buy from local kimono shops if possible. Whether they are secondhand shops or even modern kimono made by local artisans, there are plenty of options that range from very cheap to a bit on the pricier side, usually between $400-700 USD.

You can also support Jaenelle and learn more about kimono on Ko-Fi.

Recommended reading

Want to learn more about Kimono? Check out these books to learn more about the history and fashion of kimono: