The language tree is perhaps the most well-known representation of language evolution. But how accurate is it in regards to studying and comparing modern languages?

As early as the 16th century, missionaries and European travelers were noting the similarities between their mother tongue and various other languages. The idea of a common ancestral language, which we now call Proto-Indo-European, was first mentioned in 1786 by Sir William Jones in his lecture to the Asiatic Society of Bengal. Yet it still wasn’t until the mid-1800s that comparative linguistics exploded, beginning with Indo-European scholarship.

Since the 19th century, the language family concept has continued to evolve, as more language families have been included.

Language Tree Limitations

The language tree is designed as a genealogical representation of languages. That makes it easy to quickly group languages together and spot similarities. However, there are a few caveats to using this method. While it’s an incredible visual aid, especially for language enthusiasts or curious readers, it cannot fully:

- Represent language diversification

- Highlight language sharing

- Point to specific similarity types between languages not of the same family

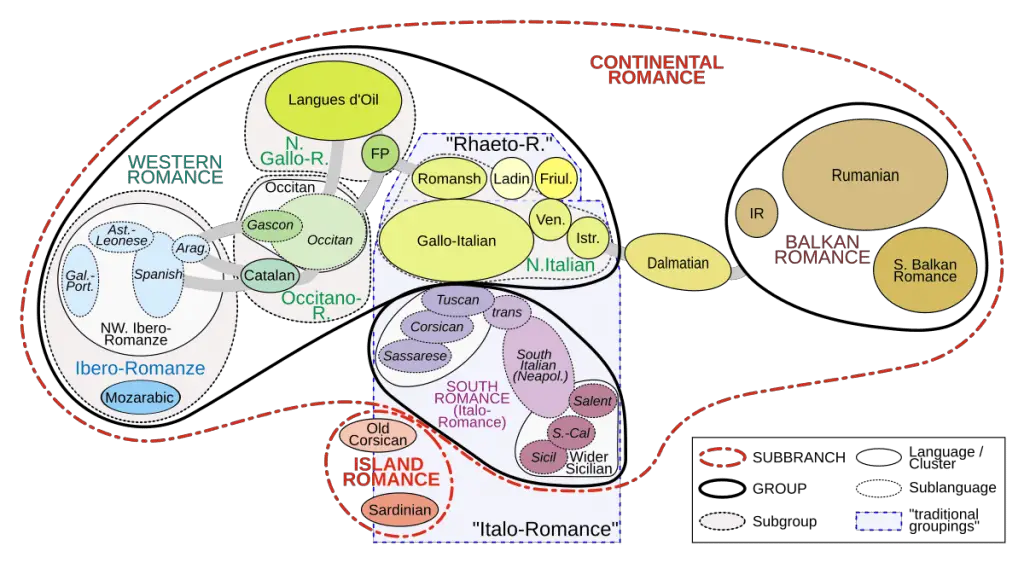

Many linguists prefer the wave model, which is composed of many interlocking circles. However, this diagram isn’t exactly space-efficient.

Another point of contention is that recent scholars have considered new micro-groupings and subfamilies, which are difficult to substantiate. Frequent loanwords and language borrowing can make it difficult to determine earlier versions of a language, and which innovations are organic or shared.

It’s all about Location

One difficulty with language grouping is determining what has been borrowed and what hasn’t. Another consideration is areal features, or language features specific to a geography.

I would suggest that historical and modern language maps provide more information than the language tree. Geography provides insight into historical language relationships and evolution.

Let’s consider the following Indo-European languages: Bengali and English. Both are considered Indo-European, yet they differ widely in grammar:

English: I watch the movie with friends.

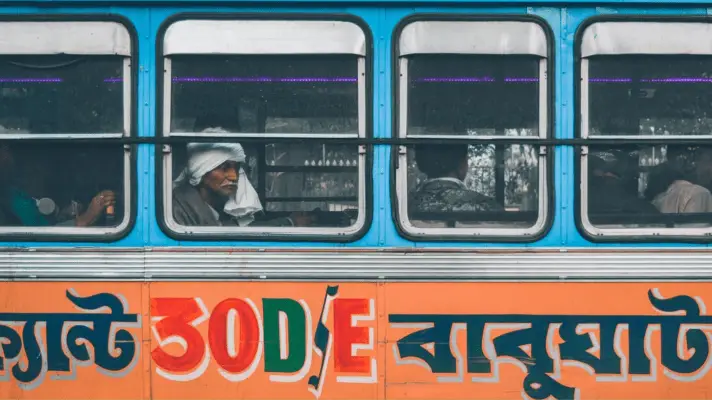

Bengali: Ami bandhudera sathe sinemati dekhi.

Literal translation: I friends with movie watch.

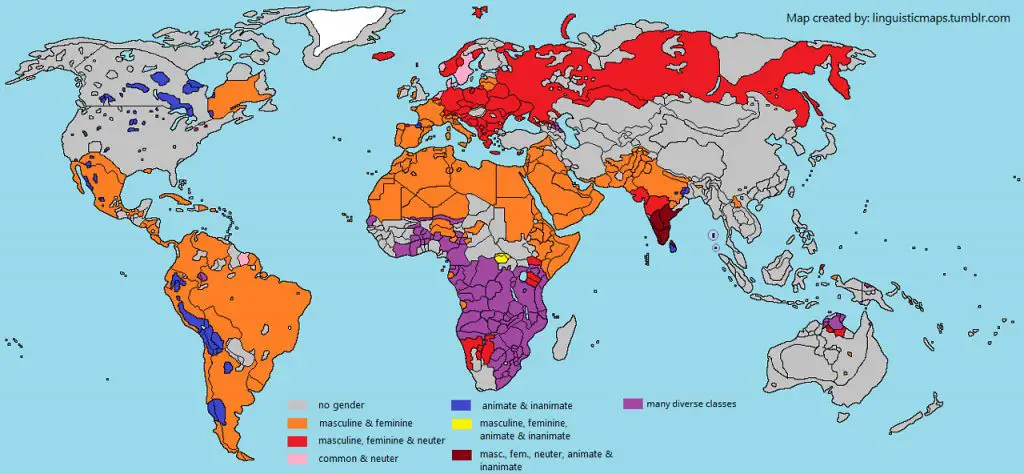

Here we see that Bengali is subject-object-verb (SOV) and uses postpositions. These structures are far more similar to other Asian languages like Japanese, Mongolian, and Turkish. Bengali also lacks gender, which more common in East Asian languages.

However, those features don’t define the languages. Because of its connection to Sanskrit, Bengali is considered Indo-European. Furthermore, you can find the same structures in some European languages. For example, German, Portuguese and Russian use the SOV structure in limited situations.

Most Indo-European languages use a subject-verb-object structure (SVO). But this is common in other languages outside of the Indo-European family tree.

Language Sharing and Influence: Arabic

Arabic, for example, uses both SVO and verb-subject-object (VSO) structures. VOS can also be found in European Languages like Spanish and Modern Greek.

Arabic also shares other grammatical norms with Indo-European languages, like the case system. Like German, Russian, and Greek, Arabic changes the endings of nouns and adjectives to match the function of the word in the sentence.

The major difference between Arabic, as a Semitic language, and members of the Indo-European family, is vocabulary. The idea is that the history of word-building is completely different between the Semitic and Indo-European families.

When we look at the Arabic word kitaab and the English book, we see no relation. Yet the methodology for creating words isn’t very different. In both languages, words are created from roots. Arabic focuses on three specific letters, while English uses a root word, which is often two-to-four characters long.

The similarities between the two families can be attributed to geography and history. Through Moorish rule in Spain, frequent Mediterranean trade and migration, we can imagine how Arabic structures and words seeped into Spanish, and later into the rest of Europe.

An interactive map that highlights language migration can help visualize language evolution, diversity, and interaction more than a genealogical tree.

From the Gulf to Bangladesh

But let’s take a closer look, this time comparing modern Indic languages to Arabic, specifically Marathi, Hindi, and Bengali.

Marathi is spoken on the west coast of India, which is separated from the Persian Gulf by the Arabian Sea. Hindi is spoken in central India, and its colloquial variant is woven with Persian and Arabic loanwords from the Mughal rule. Bengali, meanwhile, can be found in the far east.

One difference I would like to highlight is not vocabulary or word order, but instead, the use of gender as we move from west to east:

- Arabic is highly gendered, as verbs, nouns, and adjectives are changed to match the gender of the speaker or object.

- Marathi, similarly, uses gender in verbs, pronouns, nouns, and adjectives.

- Hindi, while it changes nouns and adjectives, uses less gendered verb forms. All variants of you use a neutral form, unlike Arabic and Marathi. Pronouns are also not gendered – but rather “far/formal” and “near/informal”.

- Bengali removes gender from verb forms altogether. Only some nouns are considered gendered, although adjective endings typically don’t change as they would in the other three languages.

We can see in these examples a decrease in grammatical gender as we move eastward. Other Southeast Asian languages like Thai, Lao, and Vietnamese eliminate grammatical gender completely. Despite all three regions being under the Mughal rule and being highly affected by Persian and Arabic lexicons, the grammatical structure appears to be linked more to geography.

Which language model is most accurate?

The language tree is accurate in that it gives us a broad categorization. But it lacks nuance. Understanding the relationships between languages hinges on their geography and how the borders shift over time. While the tree, wave, and map versions are all imperfect, through all three of them, we can see how language mirrors our cultural histories.

Fascinating article; thank you. The South Indian classification of M, F, N, animate and inanimate is interesting. Are the latter two separate or, as with Russian, subdivisions of other genders?

Thank you, Kevin! I believe that South Indian languages also focus more on inanimate/animate rather than grammatical gender. It’s also interesting how there are some Japanese verbs that have variants based on whether something is inanimate/animate. And while Japanese has no grammatical gender, there are ways of speaking that are considered more “feminine” as well. Gender overall is very complicated with language.

This article provides insights to grammatical model and very useful for students of linguistics.

Very interesting.

Thank you, Ajay!

Interesting post! ? I think, we should start looking at the DNA data now that more and more people get affordable access to DNA testing. I’m Lithuanian (have always been bothered by the unanswered question about why Lithuanian and Sanskrit has so much in common and which one is older) and the DNA testing of my family has clearly shown how the same group of humans, after having moved out of Africa, split up and migrated to what now is India and the Baltics. They obviously spoke the same language, so none of the languages came first. It was amazing to find. I can’t wait for the day when enough of people have got their DNA results traced all the way back to Africa – then we’ll know the whole story of the tower of Babel.

Yes, DNA is a great tool for general migration patterns. 🙂 But it only tells part of the story. My Greek DNA is sometimes categorized as being from Asian Minor (modern-day Turkey), which, after all, used to be part of the Greek-speaking empire. Combining DNA, history, and language gives a very clear view.

I have added this document to my bookmarks

I am glad to know good information. I will visit you often.