With more than 230 million people speaking Bengali as either a first or second language, it’s easy to see how there are several variations of the language. For those learning the modern language, the most noticeable difference between the Bengali dialects tends to be pronunciation.

The most common difference is in phonology, but other differences, too, in grammar and vocabulary. In some cases, such as Sylheti, there are alternative scripts for writing.

If you are learning Bengali, it may help to become aquatinted with the various dialects, as you may hear them when visiting either Bangladesh or India.

Without further ado, let’s look into the different dialects of the “sweetest language.”

The Geography of Bangla

Most students tend to be familiar with written Bengali, known as Shadhubhasha and Choltibhasha for literary and standard colloquial Bengali. And in terms of learning colloquial phrases, most textbooks focus on the standard language spoken in both Kolkata and Dhaka.

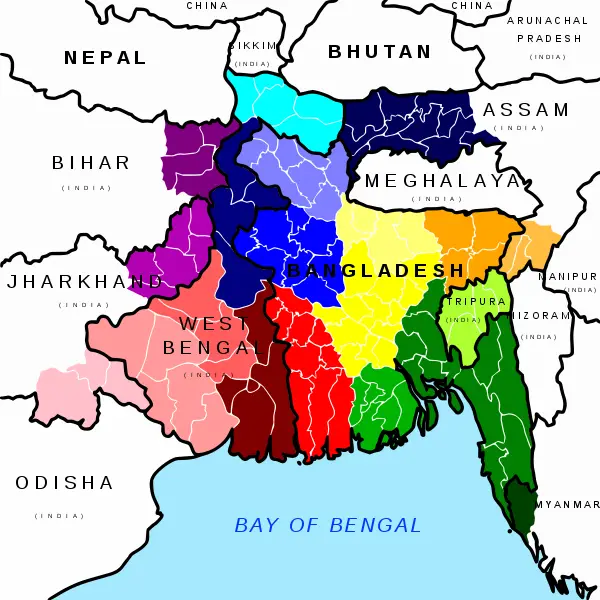

As an Indo-European language descending from Sanskrit, Bangla originates in South Asia. But the Bengali language crosses numerous regional borders. The vast distance covered by this language group has allowed different dialects to evolve over time. Within India, you can find variations of modern Bengali in Bihar, Jharkhand, West Bengal, Assam, and Tripura. And there are several dialects as well in neighboring Bangladesh, where Bangla is the official language.

Some major, but not all, dialects include:

- Varendri

- Rajbangshi

- Manbhumi

- Rarhi

- Sundarbani

- Bangali

- Sylheti

- Goalpariya

If we were to look at the prominence of the dialects geographically, we can see a clear trend. Starting in eastern Bihar, on the border of West Bengal, we Varendri and Rajbanshi. Moving north into West Bengal towards Sikkim and Bhutan, we see Rahri, Varendri, and Rajbangshi. The heart of West Bengal is Manbhumi, with the eastern side shifting into Rarhi and Sundarbani.

Crossing over to Bangladesh, we see Bangali on the western side. But moving north towards the Indian state of Meghalaya and Assam, we find Rajbangshi and Varendri. On the border between Bangladesh and Assam is a region where the Goalpariya dialect is spoken. And as we move to the southern areas of Banglesh, towards the Indian state of Tripura, are Sylheti and Chattogram speakers. Going even farther south, to the eastern edge of the Bay of Bengal and into Myanmar, there are Rohingya populations.

A Closer Look at the Bengali Dialects

What might the differences between dialects look like? Putting aside the various differences in spoken language, let’s look at example sentences with the approximate translation:

- English: I play the game on Monday at seven in the evening.

- Standard Bengali: আমি সোমবারে সাতটায় সন্ধ্যায় খেলা খেলি (Ami Sombar-e shat-tay shondhya-y khela kheli).

- Varendri: मोमबार पर सात में शाम को खेल खेलता हूं (Mombar par saat mein shaam ko khel khelta hoon).

- Rajbangshi: আমি সম্বার সন্ধ্যায় সাতটায় গেম খেলি (Ami Shombor shondhyay sat-tay game kheli).

- Manbhumi: মানভূমির মঙ্গলবারে সন্ধ্যায় সাতটায় খেলা খেলি (Monggolbar-e shondhyay sat-tay khela kheli).

- Rarhi: আমি সোমবারে সন্ধ্যায় সাতটায় খেলা খেলি (Ami Shombar-e shondhyay shat-tay khela kheli).

- Sundarbani: আমি সোমবারে সন্ধ্যায় সাতটায় খেলা খেলি (Ami Shombar-e shondhyay shat-tay khela kheli).

- Bangali: আমি সোমবারে সন্ধ্যায় সাতটায় খেলা খেলি (Ami Shombar-e shondhyay shat-tay khela kheli).

- Sylheti: আমি সোমবার সন্ধ্যায় সাতটায় খেলা খেলি (Ami Shombar shondhyay shat-tay khela kheli).

- Goalpariya: আমি সোমবারে সন্ধ্যায় সাতটায় খেলা খেলি (Ami Shombar-e shondhyay shat-tay khela kheli).

As we can see here, there are a number of differences outside of the spelling/pronunciation:

- Varendri and Manbhumi omit the pronoun here, while others maintain it.

- Varendri shares common vocabulary and grammar with Hindi or Bihari over Bengali, as seen by using positions rather than the ending -e to suggest “on.” Sylheti omits this feature completely, assuming that “on Monday” is contextual.

We can see a similar pattern in the below example:

- English: I like to drink hot tea with friends.

- Standard Bengali: আমি বন্ধুদের সঙ্গে গরম চা পান করতে ভালবাসি। (Ami bandhuder shongge gôrôm chā pān kôrte bhalobashi.)

- Varendri: मैं दोस्तों के साथ गरम चाय पीने का शौकीन हूँ। (Main doston ke saath garam chai peene ka shaukeen hoon.)

- Rajbangshi: আমি বন্ধুদের সঙ্গে গরম চা পান করার পছন্দ করি। (Ami bandhuder shongge gôrôm cha pan korar pochondo kori.)

- Manbhumi: আমি বন্ধুদের সঙ্গে গরম চা পান করতে মানোর আছে। (Ami bandhuder shongge gôrôm cha pan kôrte manôr achhe.)

- Rarhi: আমি বন্ধুদের সঙ্গে গরম চা পান করতে ভালোবাসি। (Ami bandhuder shongge gôrôm cha pan kôrte bhalobashi.)

- Sundarbani: আমি বন্ধুদের সঙ্গে গরম চা পান করতে ভালবাসি। (Ami bandhuder shongge gôrôm cha pan kôrte bhalobashi.)

- Bangali: আমি বন্ধুদের সঙ্গে গরম চা পান করতে ভালবাসি। (Ami bandhuder shongge gôrôm cha pan kôrte bhalobashi.)

- Sylheti: আমি বন্ধুদের সঙ্গে গরম চা পান করার পছন্দ করি। (Ami bandhuder shongge gôrôm cha pan korar pochondo kori.)

- Goalpariya: আমি বন্ধুদের সঙ্গে গরম চা পান করতে ভালবাসি। (Ami bandhuder shongge gôrôm cha pan kôrte bhalobashi.)

Again, we can see that Varendri has significant vocabulary shifts compared to the other dialects, which retain most Bengali vocabulary. Manbhumi, Rajbanshi, and Sylheti also show variation in verb conjugation.

But let’s dive a little deeper, starting with the difference between the standard and colloquial language.

1. Shadhubhasha and Choltibhasha

In modern Bengali, there are two main stylistic systems: Shadhubhasha and Choltibhasha. The latter is the current standardized written form of Bangla, which is promoted by the literary giants of Kolkata, such as Peary Chand Mitra and Pramatha Chowdhury.

These two dialects of Bengali have different phonology, grammar, and vocabulary. They differ in grammatical gender, verb inflections, and personal pronouns. Both also have different uses, with Shadhubhasa being reserved for high literature and Choltibhasa being used for everyday communication.

Both, however, are what you will likely learn in a textbook. Furthermore, the colloquial variations in Bengali textbooks pull from Kolkata or Dhaka speech, also called the Rahri and Bangali dialects, respectively.

General Differences Between Western and Easter Dialects

In terms of phonology, Western Bengali has only one rhotic /r/, whereas Eastern Bengali maintains the rhotic /r/ and its devoicing counterparts, dd’ [dd] and ddh’ [dd]. The distinction between these realizations is clear in West and Southern Bengal, but in Eastern dialects, it can sometimes become similar to the phonology of Assamese.

There are also various phonological alternations between the Western and Eastern dialects. Some speakers of Eastern Bengali use kh’ [xH] and ph’ [fF] as their standard phonemes, while some dialects substitute dd’ [dd] with bh [bh].

The rhotic /r/ can be realized either as a tap or a palatalization, depending on the context. This is different from dd’ [dd] and its devoicing counterparts, which are always voiced.

Moreover, some variants of Eastern Bengali do not distinguish aspirated velar and labial stops from their unaspirated counterparts. The unaspirated gh [gh], jh [dzh], and dd’ [dd] can be replaced with bh [bh], while the voiced gh and jh are always pronounced.

Finally, the dialects of Eastern and Western Bengali are similar in that they both use a combination of aspirated and unaspirated voiced stops. They do, however, share phonological features with Assamese, such as the debuccalisation of sh [S] to h [h].

2. Varendri

The Varendri dialect is one of the major dialect groups in Bengali. It is spoken in the Malda division of West Bengal (formerly part of Varendra or Barind division) and the Rajshahi division of Bangladesh, as well as in some adjoining villages in Bihar bordering Malda.

This dialect has been influenced by Dravidian and Kol languages and has many non-Aryan words. Its vocabulary also contains words from other Indian languages, such as Hindi and Urdu.

Its grammar is complex, with finite verbs split into two groups based on the accidence of their indicative and imperative forms. It is also a polysynthetic language.

In order to distinguish between the tenses of a word, a grammatical marker called an inflection point is used. This is a point at which a verb’s inflection changes, such as if the verb is in the present or future tense or if it is an honorific form.

A second inflection point is used to indicate whether the verb is a direct object of a noun or a prepositional phrase, and it is often accompanied by an inflection point that indicates the number of times it occurs. The accidence of the second inflection point is generally more complex than the other inflection points.

Phonologically, the Varendri dialect is similar to standard Bangla in some respects. It has a relatively high level of vowel harmony, the use of a common pronunciation of i (i) and u (u), and the separation of geminate clusters born out of conjunct consonants in spoken form.

3. Rarhi

Rarhi is a Bengali dialect that is spoken in most of South West Bengal. It is also spoken by Bengalis in Tripura, southern Assam and in the Indian union territory of Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

The language is divided into a number of dialects, which differ in their grammar and vocabulary. These dialects are mutually intelligible, but they have different pronunciations and phonologies.

Compared to the standard writing form of Bengali, spoken Bengali has a much greater level of diglossia and variation. The formal written Bangla is based on the Rarhi dialect of Southern West Bengal, but spoken varieties include Choltibhasha, Ancholik, and Gramyo Bangla.

This dialect is spoken in Kolkata and the Nadia district of West Bengal. Therefore, Rarhi is similar to the standard written form of Bengali but has Persian and Arabic words rather than Sanskritized ones.

4. Rajbangshi

Rajbangshi is a dialect of Bengali that is spoken in the eastern part of Bangladesh. It is a very popular dialect of Bengali, and has a distinctive culture unique to the region.

The pronunciation of the dialect is very similar to standard Bengali and has some common features with Hindi, but it has its own distinct characteristics. The main difference between the two is that in Rajbangshi /s/ and /z/ are pronounced like /dZ/, as opposed to their English pronunciation.

Another feature of the dialect is that it has a strong tendency to mix up /s/ and /z/ at the time of forming plurals. This is a feature shared by many other Indian languages and can be seen in the way people speak Hindi, Sanskrit and Urdu.

Pronunciation of the dialect also has a lot of variation. The speakers in rural areas tend to pronounce /z/ more like a stop than a fricative; this is reflected in their English.

In contrast, the speakers in urban areas tend to pronounce /s/ more like a voiced sibilant than a stop. This is a phenomenon shared by other dialects of Indian languages, including Gujarati.

Some of the other pronunciation characteristics of the dialect include a weak nasalization of sibilants (), a tendency to pronounce long vowels with a hard velar, and a very low tone level. The pronunciation of the dialect also reflects its societal position in the region and is often influenced by its traditional religion.

5. Sundarbani

The dialects of Sundarbani are found in the northwestern part of Bengal, including the city of Sundarbans. They are influenced by the language of the surrounding area, including Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. They are also influenced by the local language of Kolkata, which was the language of the early colonial administrators.

In particular, Sundarbani has many words that are borrowed from English. The most common of these is gnyj gonj, which is used in names of hundreds of cities and towns across Bengal, such as nbaabgnyj Nobabgonj and maanikgnyj Manikgonj.

6. Sylheti

Sylheti is an East Indo-Aryan language spoken in the eastern part of Bangladesh and in border areas of Assam, India. It is often ambiguously considered an independent language or a dialect of Bengali.

The Sylheti language, named after the city of Sylhet in today’s Bangladesh, is principally spoken to the west in the Surma river valley that today comprises four districts, or zila (Sylhet, Sunamgonj, Hobigonj, and Moulvibazar) in the Sylhet Division in north-east Bangladesh and to the east in the Barak river valley that today comprise three districts, or zila (Cachar, Hailakandi, and Karimgonj), in the Barak Valley Division in the state of Assam, India.

Its history is influenced by Hindu, Sufi, Turco-Persian and native ideas. It is written in a unique script called Siloti Nagri, which fell out of usage in the mid to late 20th century but has been re-discovered and revived today. The earliest documented works of Sylheti literature date back to the medieval period. These include the earliest known Sylheti biographies of the great Muslim saint Shah Jalal and his 360 disciples, who came from all over the Arabian Peninsula to the city of Sylhet with the mission of overthrowing Raja Gour Govinda, a Hindu king who was hostile to Muslims.

Sylheti differs from other regional Bangla dialects as it has significant deaspiration and spirantisation, as well as the additions of tone. While many native Bengali and Sylheti speakers find the two languages incredibly similar, there is a movement to have Sylheti viewed as a separate language.

7. Manbhumi

Manbhumi Bengali, formerly known as Purulia Bangla, is a dialect of the Bengali language that is spoken in eastern India. It is one of the dialects that have been influenced by Odia and has some similarities with neighboring dialects in Bihar and Orissa.

After the independence of India, Manbhum district was merged with Bihar state (present West Bengal). This resulted in restrictions on the use of the Bengali language and the forcible imposition of Hindi on the people of Manbhum. This affected the majority of the people in the region.

In the midst of this, a movement was started to restore the use of the Bangla language in Manbhum and to demand that the district be included back into Bengal. It was made into a pan-Bengal apolitical movement, and many prominent personalities joined it, including Atul Chandra Gupta, Dr. Prafulla Chandra Ghosh, and Bimal Chandra Sinha.

The movement spread across the entire district, with protests and law disobedience movements being held throughout the year. In 1956, a non-violent march was organized from Pakbirra village in Manbhum to Kolkata. This was led by the Lok Sevak Sangha.

The movement also spawned a large number of periodicals and magazines, most of which were published in the local language. This helped to spread awareness and the news of the movement. Some of these included: “Mukti,” “Marmabani,” “Kalyan Barta,” “Harijan Kalyan Sangbad,” “Palli Sewak,” “Tapoban”, and “Agragami.” Tusu songs were also written and performed in this dialect to promote the movement.

More Resources for Learning Bangla

If you’re still looking for resources to improve your standard Bengali, here are my favorites for jump-starting your experience:

- Learn the Bengali Alphabet

- The Complete Bengali (Beginner to Intermediate)

- Colloquial Bengali

Both Complete Bengali and Colloquial Bengali use transliteration to assist your learning. I love the in-depth pronunciation sections in Complete Bengali. Both also include free online audio. Once you complete these books, I highly recommend watching Bengali movies and TV series on Hoichoi.